Pasts, Futures: On 'City in a Garden' & Jeff Mills’ Futurism

I took the weekend to engage in knowledge-building. Viva Acid, hitting its five year anniversary, threw parties and panels for the current and aspiring Chicago DJs hungry for engagement beyond the dancefloor. I attended Saturday's panels, learning directly from those maintaining the infrastructure of dance music's cultural impact through mentorship, resource sharing, and archival preservation. A special shoutout to Aria Pedraza's growing Midwest Rave Culture Archive.

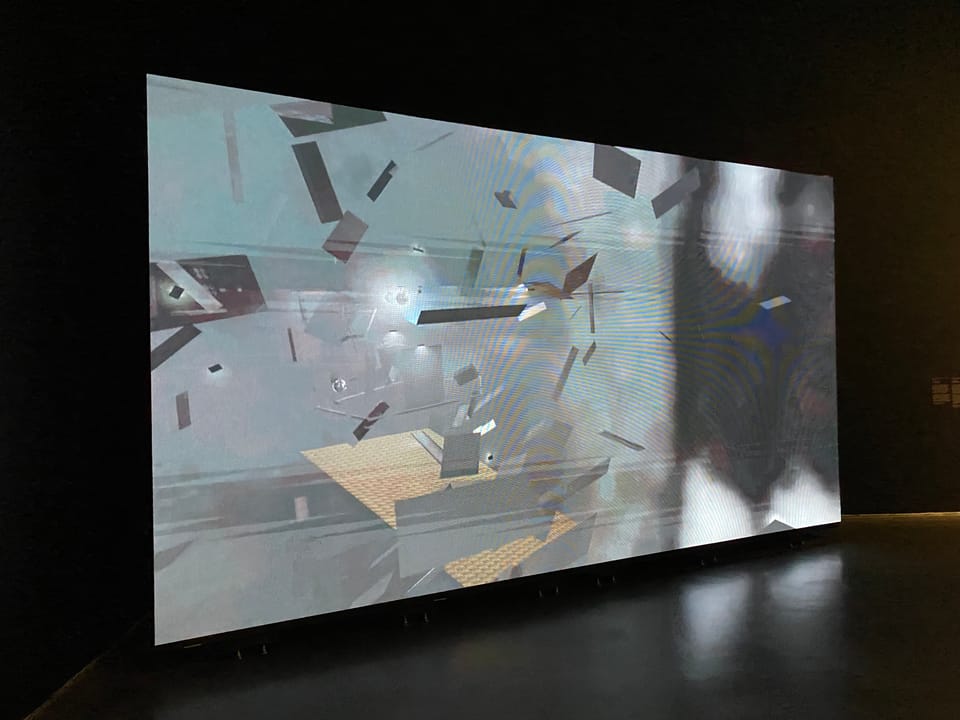

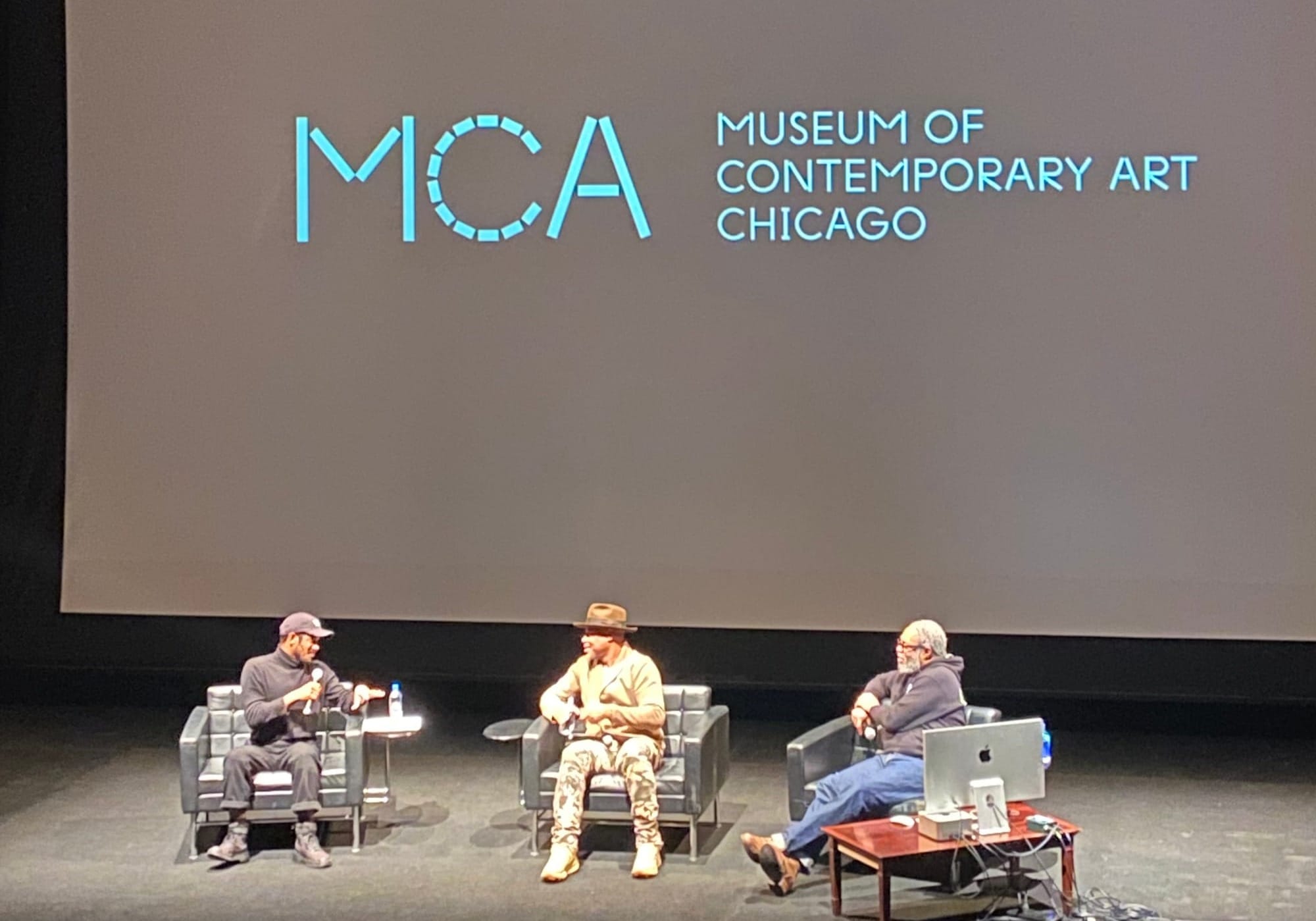

Sunday morning, the Museum of Contemporary Art hosted dance music pioneer Jeff Mills and his collaborators Jean-Phi Dary and Prabhu Edouard, altogether forming Tomorrow Comes the Harvest. The MCA has produced an array of programming in partnership with Metro / smartbar in recent years, supporting the City in a Garden: Queer Art and Activism in Chicago exhibition.

Dance music has always been queer, to me. Art school introduced me to wonderfully creative new friends, who lived so differently than I had in suburban Chicago. Partying brought me to nightclubs in what's now known as Northalsted, throbbing bass available almost every night of the week. I quickly became immersed in a scene of up and coming DJs throwing DIY parties and hosting residencies at Berlin, East Room, and smartbar. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the speed of the scene, as it did everything else, with the pieces coming back together over time.

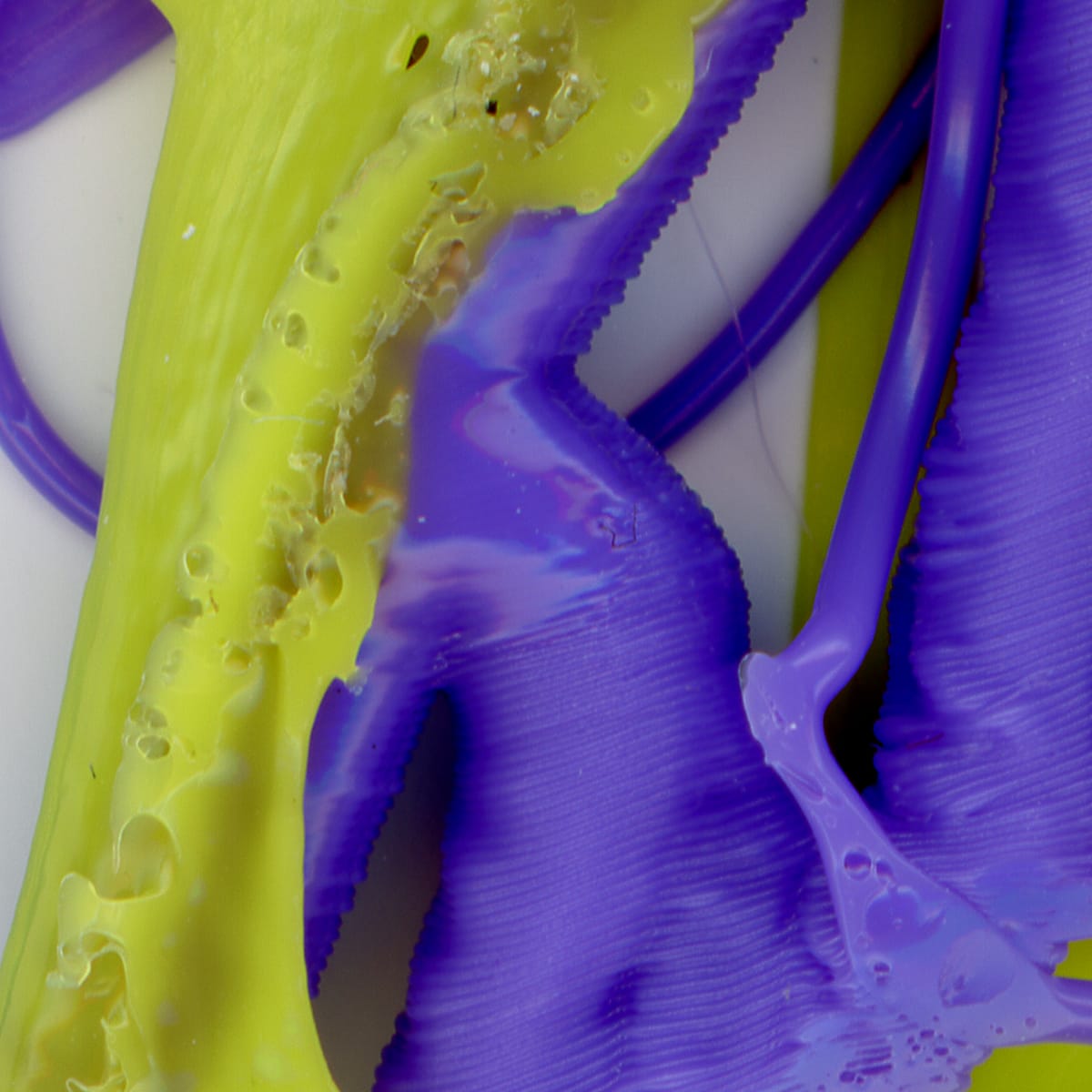

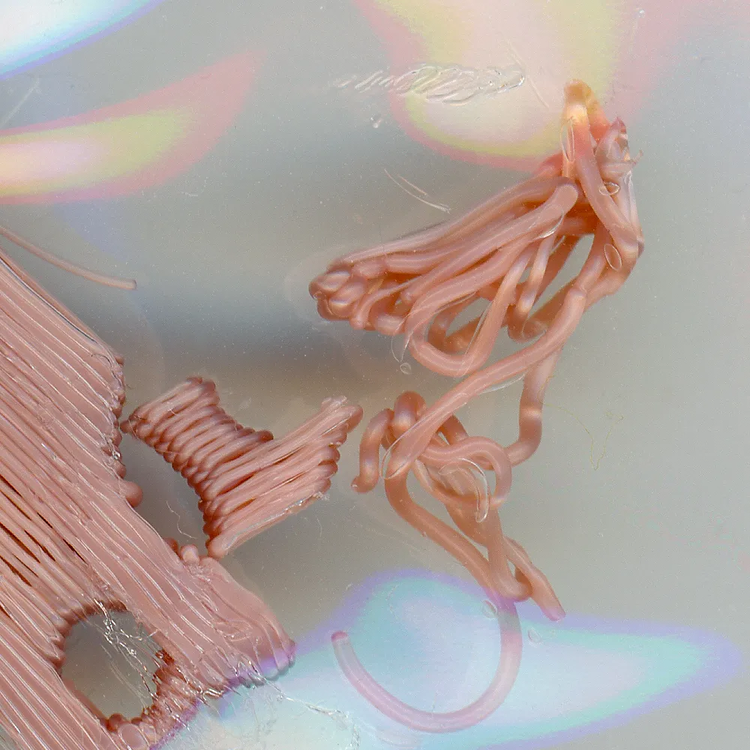

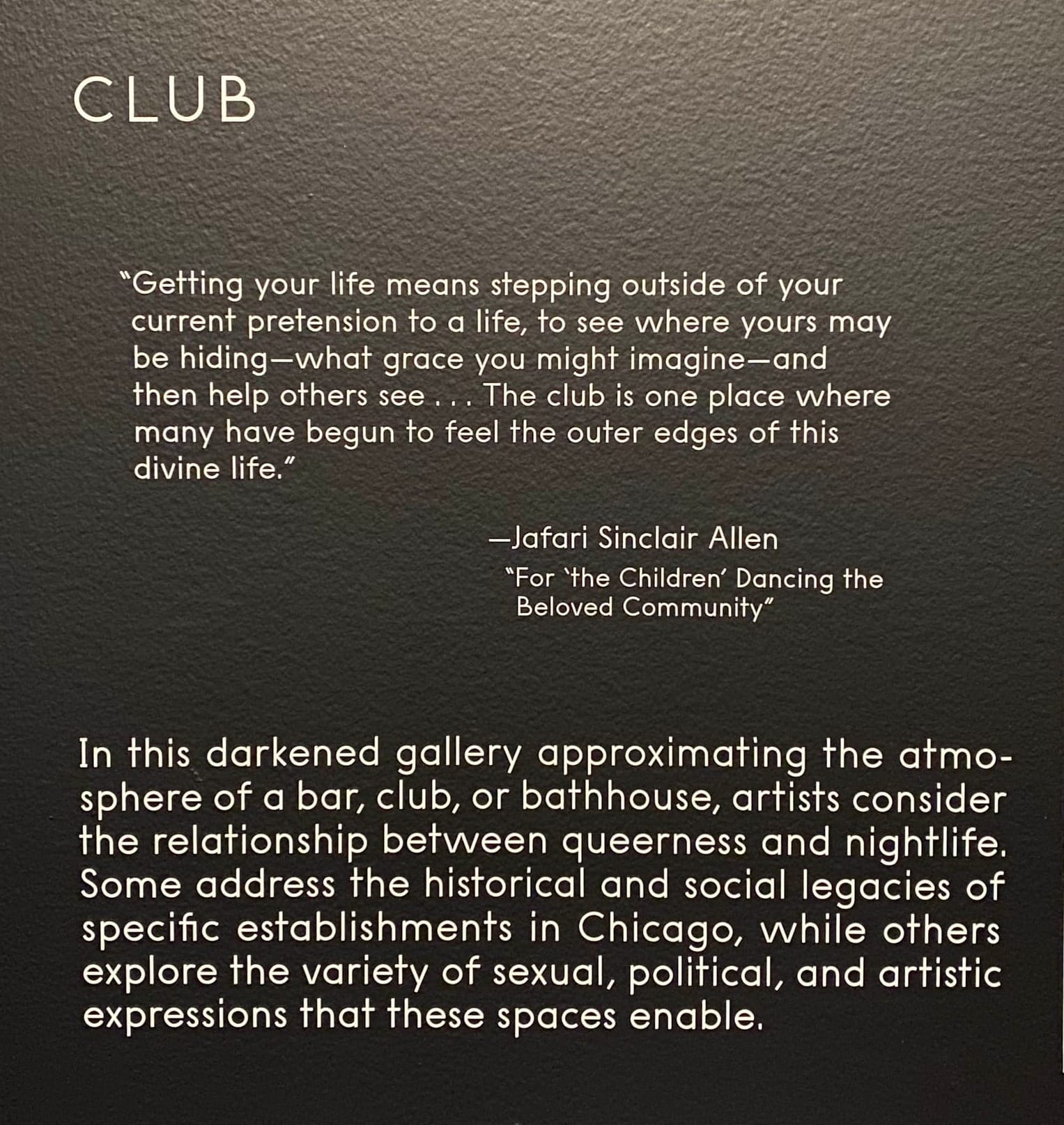

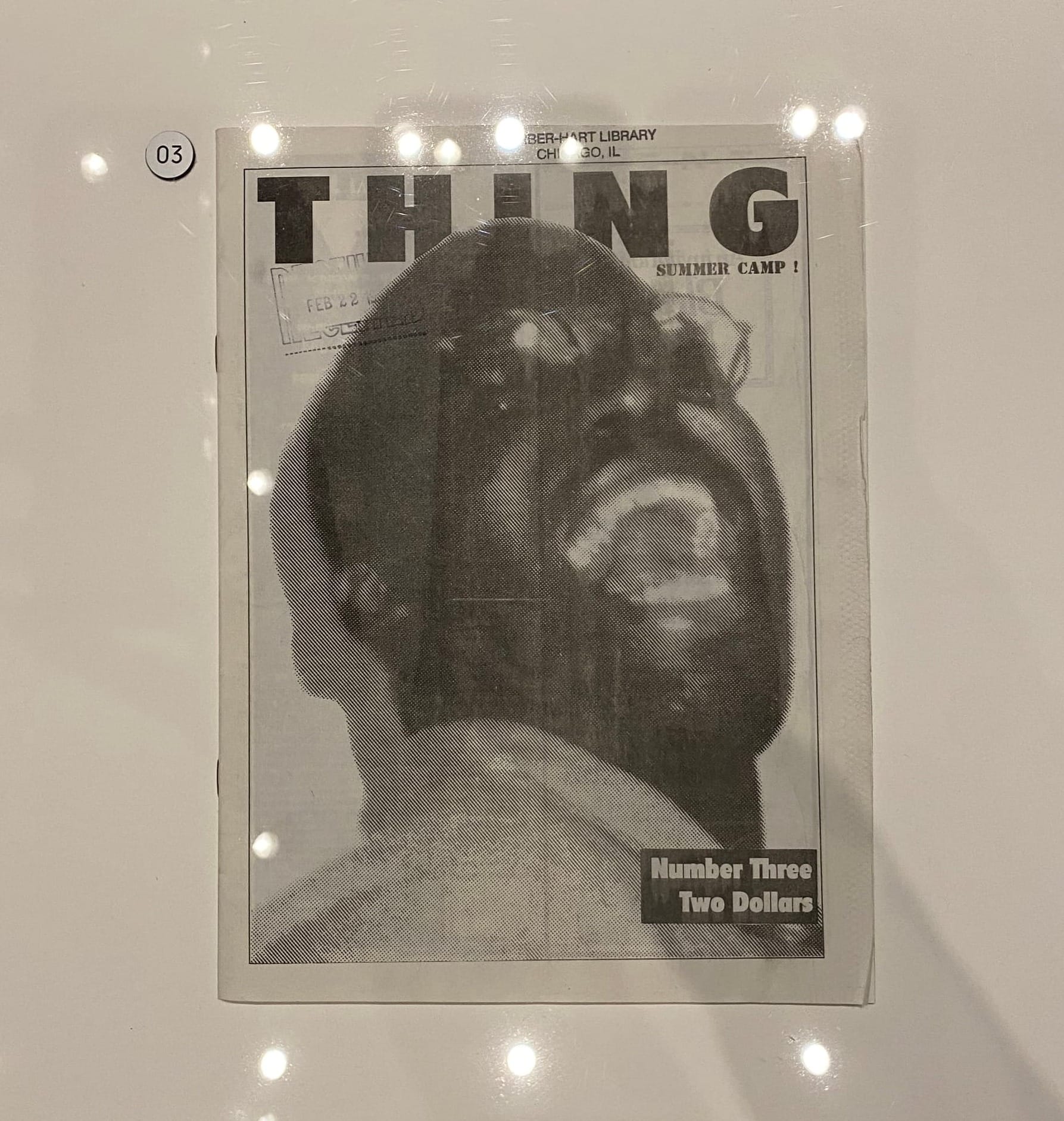

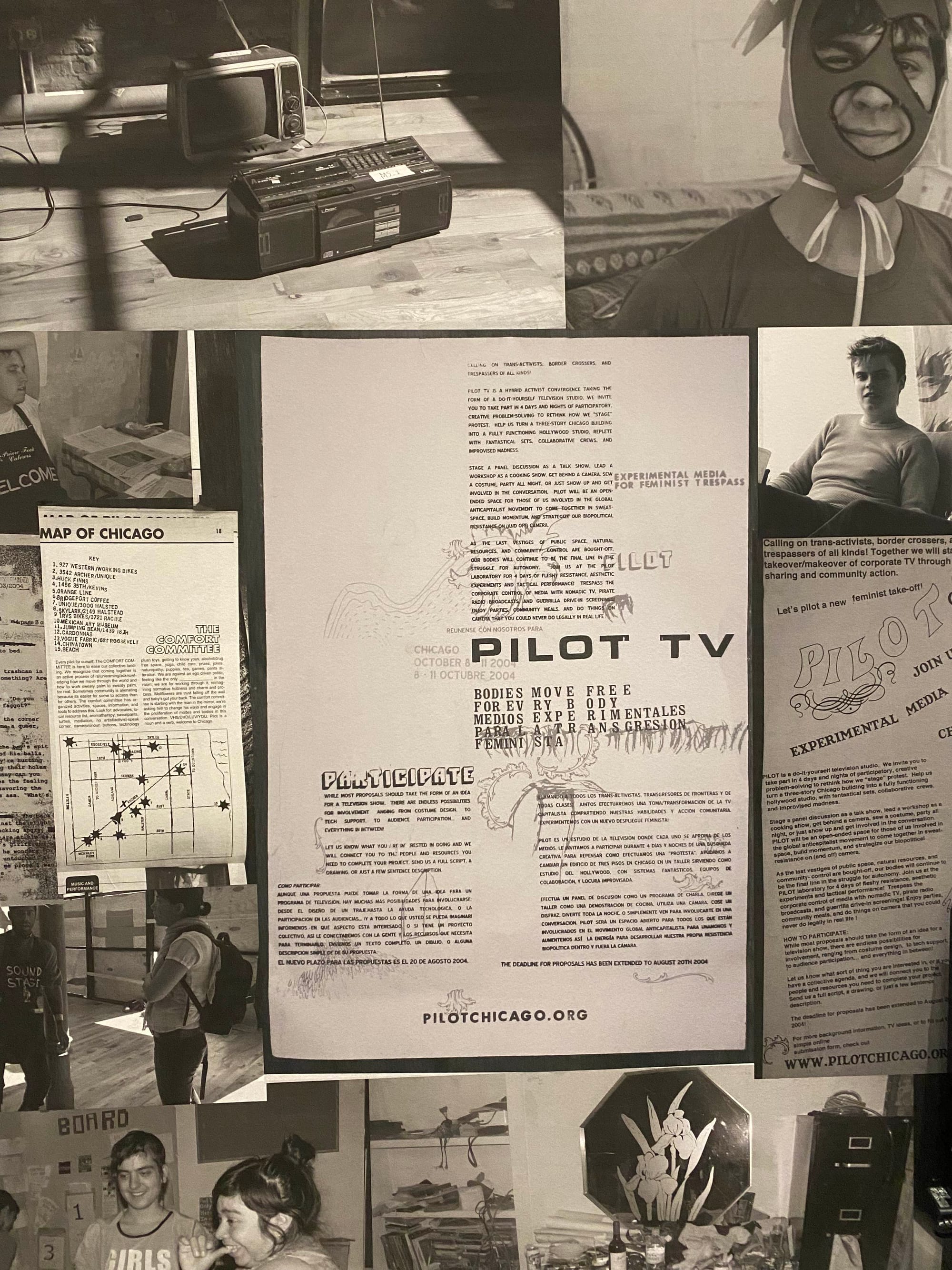

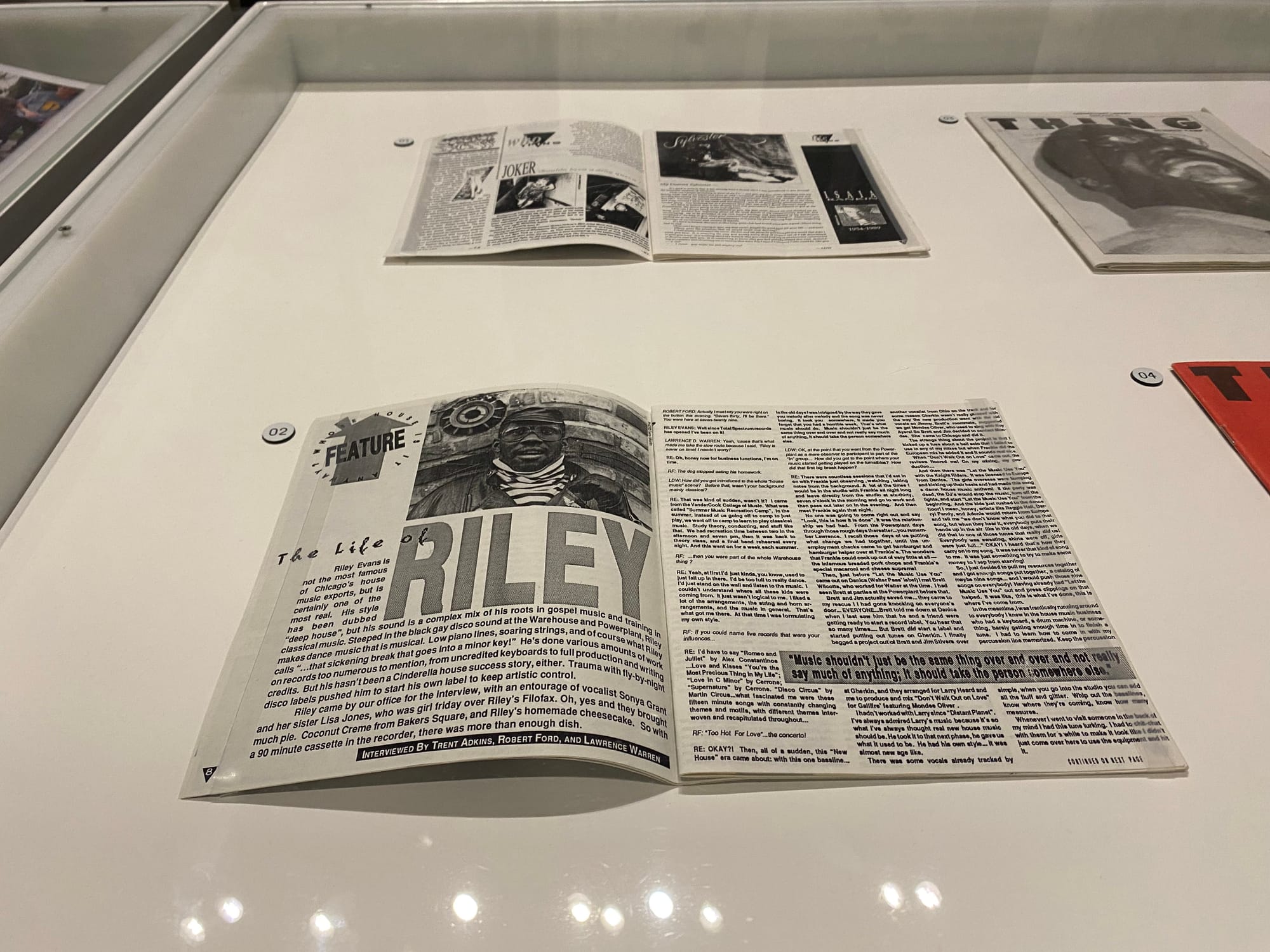

In the year between these talks, I walked through the exhibition at the MCA. Experiencing this in the years after two of those clubs have closed or shapeshifted, as well as my own hiatus from the lifestyle of nightlife, I was brought to tears. It was incredibly cathartic to have such an immersive experience in an exhibition.

Precluding gigs at Metro/ smartbar, the first of these conversations included musician Robert Hood, writer DeForrest Brown Jr., and filmmaker Arthur Jafa in 2024, Hood being a fellow founding member of Underground Resistance alongside Mills. These talks were not specifically aligned with City in a Garden, but they are in spirit. To a packed room, author of Assembling a Black Counter Culture Brown Jr. was eager to be the rhetorical bridge between Hood and Jafa's shared vision of collaging histories to represent possible futures. The conversation was recorded and is available here.

Nearly a year later, this morning, Jeff Mills sits on the same stage, in conversation with Resident Advisor's Kiana Mickles. It's earlier in the day than the cozy afternoon that held the Brown Jr./Hood/Jafa trifecta, the room with much more air and intimacy. From the start, Mickles is interested in guiding us through the story of Mills' life through the many collaborations he's engaged in. He happily obliges, telling us first about his involvement with the band Final Cut and the influence of an industrial sound. On influences, he dives a bit deeper, explaining how the ubiquity of jazz on the radio and the discipline of his high school band instructor–a former saxophone player for Duke Ellington–encouraged a deep focus on learning all of the opportunities that instrumentation provides: "it's an extension of who you are and how you feel."

For Mills, collaboration is a specific and intentional act: on the formation of Underground Resistance, he emphasizes that if "we say the right thing at the right time for the right reasons, we could go further." Like Hood and Jafa, Mills communicates future possibilities through machines, drawn from the experience of living through oppressive times, understanding the boundaries that the music industry and institutions construct that the three artists utilize to their advantage or break down entirely. Mills tells us a story from his childhood, when the Uprising of 1967 in Detroit spurred martial law in his neighborhood. "It was a dark time," he reflects. Moving the family vacation up early, his parents took him and his siblings up to Montreal for Expo 67. The oblique futurism of the world fair was such a contrast to his experience in Detroit that it opened him up to the possibility of imagining otherwise.

Mickles encourages him to speak further on his positive outlook about the future, inviting him to embellish on his love for science fiction and outer space. Mills excitedly recounts the distribution hubs of comic books at train stations throughout the Midwest. His father's career as a civil engineer enlightened him to the ways that the "media machine" was actively shaping narratives about the space race. Some things haven't changed. Emerging technologies can be a conduit for imagination and knowledge; while the creators of these technologies have intentions for what their utilization may implicate–such as how they may profit from said utilization–what the threshold of its larger social and cultural meaning entails is directly influenced by its distribution and representation in public. One such technology, and Mills' instrument of choice, the drum machine, is a "machine that everyone can relate to," and he believes, as do I, that the response it creates is universally appealing. Mills then historicizes the connection between the public's understanding of technology and a communal assuredness towards progress: witnessing emerging technologies becoming commercially available, "we all understood what we were working towards." The end of the century was the threshold of meaning for Mills and many of his peers. But, of course, as the artist and writer articulated throughout the conversation, we are now a quarter of a century past the dawn of that new millennium.

So, what now? "There is little reason to not be optimistic about the future," Mills asserts. It may feel heavy now, he says, but "time moves fast, no matter how chaotic things are, there will be a time where it will slow down." I was suddenly reminded of my experience walking through City in a Garden, the weight of the near-decade that has passed since I first heard what Chicago dance music sounded like. He emphasized that we need to keep as open of a mind as possible toward the future, and that much like the many spheres of knowledge produced through the 20th century, we will face similar, if not the same, challenges through this one.

While dance music cannot be contained, these conversations at both Viva Acid and the MCA, as well as the archival and multimedia City in a Garden exhibit, represent possibilities for world-building and imagination that music can produce through technology. It was also a stark reminder of how recent the history of dance music is, and how we as DJs, enthusiasts, and dancers have a responsibility to continue to facilitate these conversations, exhibitions, collections, and community building.

City in a Garden: Queer Art and Activism in Chicago is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art until May 2026. Please go see it.