Against AI: Library Trends

The following are my own remarks, edited for clarity, from a webinar produced by Library Trends.

Before I became a library worker, I was, and still am, a researcher. My Master’s research into deepfakes from 2019-2021 gave me much of the theoretical knowledge [on artificial intelligence] needed to pursue the work that I’m discussing with you all today.

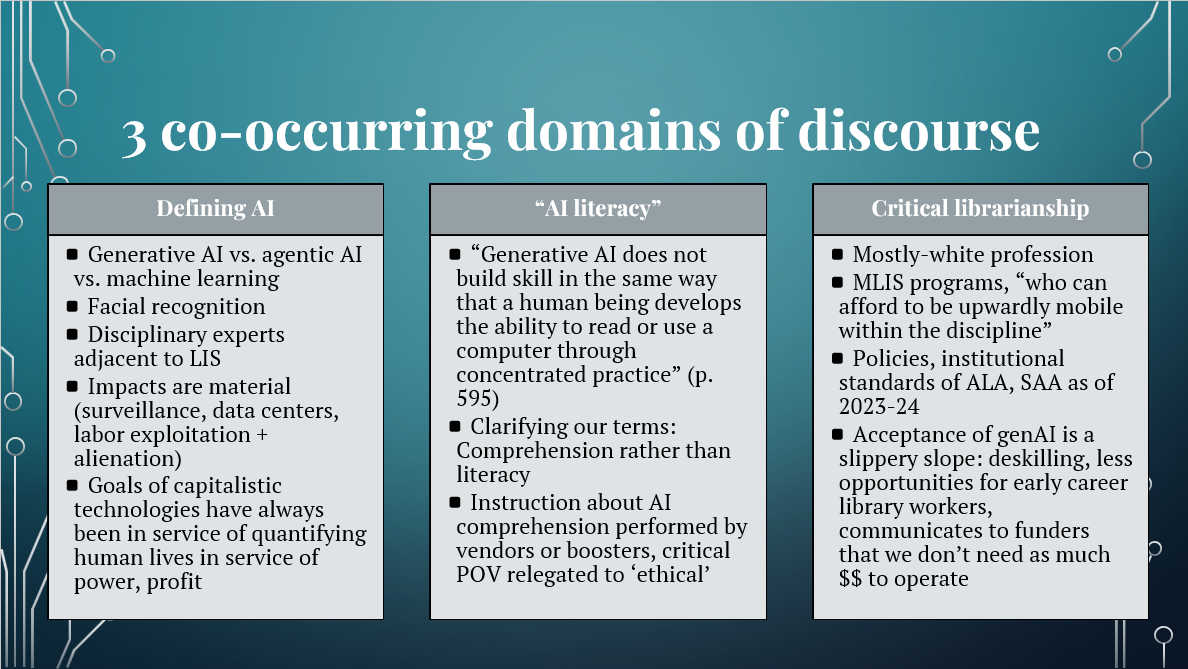

Entering into librarianship, I noticed that there were three domains of discourse occurring in response to the commercial popularity of generative AI. Applications had moved out of niche internet communities and into the mainstream, advertised as services to meet social needs. Based on the array of use cases pitched in professional development for library workers, I felt that there was some abstraction regarding what AI is, and what the companies that produce what we understand as AI intend it to be.

In the article [“Against AI: Critical Refusal in Library,” 2025], I attempt to draw some lines in the sand about what I’m talking about when talking about AI – I focus on generative AI for purpose of the special issue, but make reference to this moment of confusion about what AI is, and how library workers have been engaging with artificially intelligent programming like machine learning for many years. Another type of AI is agentic AI, the type of AI that is more functionally akin to robots and is posited as being “so good” that it could somehow totally replace the labor of human beings. To me, this just sounds like the willful development of digital slaves. In an upcoming column for Information Technology and Libraries, I think about agentic AI as first utilizing “gen[erative] AI as a building block.” Second, that “[t]he technology industry itself imagines an ouroboros-like future, where compounded systems of many large language models and synthetic media applications [run] society autonomously, only steered by the ‘right’ kinds of men.”

I’ll reference in a moment the material impacts of generative AI, namely the systems and organization of labor that make generative AI possible: data workers and data centers. But before we get there, I want to make some clarifying points about my perspective within the article. I spend time discussing the term “AI literacy,” and posit the word “comprehension” over “literacy,” because “generative AI does not build skill in the same way that a human being develops the ability to read or use a computer through concentrated practice.” So, in the learning situation, we come to knowledge through the synthesizing of information through tools, such as books or texts found on computers–but that ‘coming to knowledge’ inherently involves the use of our own brains to qualify new information in reference to information that we’ve already absorbed. Literacy takes that ‘coming to knowledge’ out into the open, in demonstrating comprehension through the application of knowledge in external situations from that initial moment of learning. So, “AI literacy” cannot mean learning “with” ChatGPT. ChatGPT tells you things based on what OpenAI has decided to scrape from the web and exploit workers to train.

Generative AI produces outputs through statistics, and the training of generative adversarial networks by data workers. The combination of these two aspects–math and labor–are at a massive scale, and quite literally tell you what you want to hear. And, at an enormous ecological cost: Truth Dig reported yesterday that OpenAI’s “audacious long-term goal is to build 250 gigawatts of [electrical] capacity by 2033”–which means that OpenAI intends to build enough electrical power that is “almost exactly as much as used by India’s population of 1.5 billion people.”

There is much more to say about this, but in the interest of time, I want to make a quick point about critical librarianship, and think about why it’s important to be critical about AI.

In professional development settings, instruction about generative AI can tend to be performed by vendors or what have been termed “boosters,” folks who are positively encouraged by the applications and want to see their integration into existing services. In these settings, boosters leave little or no space for the critical point of view–which, in a rhetorical way, makes sense. Why would they want to shine light on what makes the technology unappealing? Occasionally they leave room for “ethical impacts,” which situates antagonism and dissent as something separate from AI's epistemology, or the way we come to knowledge. But for myself, I find it incredibly important to take a stance that is antagonistic. Briefly, I think disciplinary-wide acceptance of generative AI is a slippery slope: it encourages deskilling, meaning less opportunity for early career library workers, and communicates to funders that we don’t need as much money to operate.

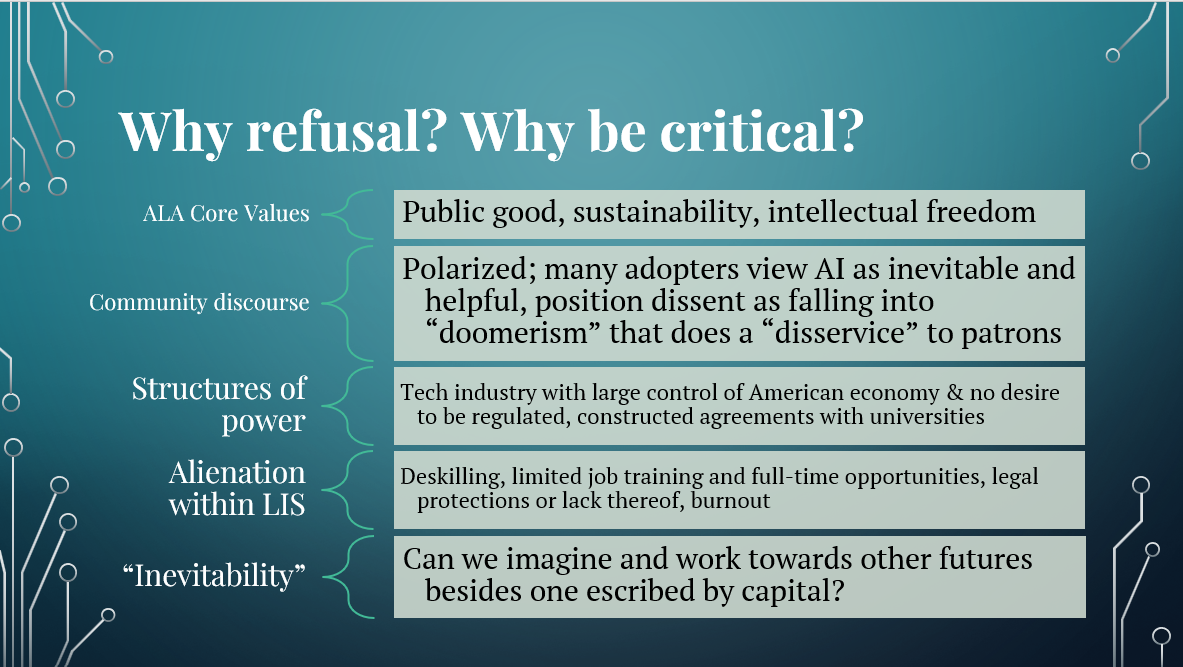

So, why refusal, why be critical? Within the article, I consider these 5 tenets as supporting my argument for refusal.

First, we can point to ALA’s Core Values, some of which are to serve the “public good,” maintain and support “sustainability,” and propagate “intellectual freedom.”

Second, how libraryland discusses AI sets the stage for analysis, especially when challenging dominant narratives and thinking about power. Conversations are “polarized; many adopters and boosters view AI as inevitable and helpful, [while] position[ing] dissent as falling into ‘doomerism’ that does a ‘disservice’ to patrons.” While I am making general statements here, during programming that I’ve conducted on the job as well as in questioning boosters about their own stance, that is a common response. That by taking a stance of refusal we are limiting patrons–when, in reality, patrons are being limited by the technology companies that want to, and are actively seeking to, insert their products without our consent into libraries, schools, and public infrastructure.

That brings us to our third tenet: structures of power: that the “technology industry” has a “large control of the American economy” with “no desire to be regulated:” this is the “AI bubble” that will inevitably pop.

Fourth, as I mentioned earlier, I think there is a feeling of alienation within LIS that contributes to the appeal of generative AI as a solution to problems that are, inherently, issues within the workplace and social environment.

Fifth, this idea of “inevitability” has captured much of the discourse. The idea of “adapt or die” is toxic, and is aligned with the white supremacist notions of “binary thinking, perfectionism, and worship of the written word.” Instead, I ask, can we imagine and work towards other futures besides one escribed by capital?

I encourage you to read the article, and when you do read it, know that I am not looking to “blame workers for turning to generative AI in stringent times of need, rather, [I] understand that the harms are facilitated by power- and money-hungry corporations that control technological infrastructure” (p. 601). I, of course, implore you to use your agency to consider your stance on generative AI, and AI more broadly, as one that is critical, but I also understand that we are all in vastly different working conditions across librarianship and information work. That said, there could be situations where you can get into discussions with leadership, with your IT department, and with vendors about AI. See if your institution or union has a policy about AI. Get involved, voice your concerns.

To attempt to encapsulate all of what I’ve discussed today, and more discussion in the article regarding facial recognition, environmental harms, and researchers to keep an eye on: I think that we “should refuse generative AI because it is a ‘destructive force’ that is infrastructurally racist, marketed as a solution to increasing socioeconomic disparity while gleefully scraping all possible traces of digital and digitized labor…[it] does not magically produce information with integrity without requiring further human scrutinization, and creates an unnecessary excess of energy emissions that is detrimental to our ecosystem” (p. 601).

To wrap, here is where my research into AI and librarianship has taken me. I’m curious about how infrastructures of information work are established, and connecting our labor in LIS to those in media and technology. And, some big ideas: is there an AI-industrial complex? I think so. I’m interested in examining if there are any benefits to data centers beyond the aforementioned “adapt or die”-style rhetoric, including if data centers will extract economic capital that is available to libraries.

Again, thank you all so much for attending today’s webinar. Here’s where you can find me on social media. I’ve also included a link to a recent appearance on the podcast librarypunk where I talk more about refusal of AI in librarianship. Thanks!